Remember: It costs nothing to encourage an artist, and the potential benefits are staggering. A pat on the back to an artist now could one day result in your favorite film, or the cartoon you love to get stoned watching, or the song that saves your life. Discourage an artist, you get nothing in return. Ever.

Kevin Smith

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… The Cover of Revive Magazine

I’d first thought to do a homage to classic psychedelic poster art, but I wanted to be less obvious and more creative. The final cover had a number of different influences: the frame is gold as a reference to the yellow frame around every issue of National Geographic; the rest was inspired by Alex Grey, whoa painted a character he called Cannabia, a feminine incarnation of the cannabis plant with a hint of sacred art about it; his Cannabia was green, but I went with the color purple as a reference to Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze.” The character wears a golden crown with emeralds stylized to resemble cannabis leaves; her eyes glow with a green light in reference to the idea that cannabis can provide insight and inspire ideas.

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… The Concept of “Aesthetic Arrest”

My fundamental approach to art comes from James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” (1916). Joyce states that art achieves its most transcendent state when it holds the viewer in what he called “a state of aesthetic arrest;’ when the image makes such an impression that the viewer is held in place by fascination with that image. For that brief, powerful moment, they’re not thinking about anything else; they just have to stop and LOOK at it. The moment ends quickly, but it can be one of the most sublime of human experiences.

Perhaps my fondest experience of aesthetic arrest is one that didn’t happen to me, but to my wife Yvette. While we were still dating, we went to the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg. One of the prominent works on display bore the wordy title: “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln:’ (1976). I knew the painting well, so I knew what to look for, but Yvette didn’t, and had no idea what she was supposed to see – there’s a first time for everyone, after all.

I positioned myself behind her as we looked at the painting up close, at the backside of Dali’s wife and muse standing before the sea, and then we both began to gently back up the required twenty meters while I said over her shoulder, “Okay, now tell me when you see something … ” And when she did see Lincoln, when her eyes widened as she saw the totality of what Dali had painted and experienced that moment of aesthetic arrest for herself, I felt joy for her – and for myself, for she’d given me a way to vicariously relive an experience I could no longer have with that painting – there’s a first time for everyone, but the second will never be the same, because you can’t un-see Lincoln once you’ve seen him. That’s why the experience is one to be treasured.

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… The Creative Process

My creative process is geared toward creating that reaction in the viewer in any way I can. All other decisions I make – which materials, what composition, what colors – are made with this in mind. I use markers to amaze people who can’t believe I could obtain this result from markers; I use the level of detail and intricacy that I do to hold viewers in place while they contemplate and take in that detail and intricacy. I do it in order to earn the undivided attention of a viewer that is usually only going to look at something for a fraction of a second before moving on to look at something else; if I’ve done my job right, the viewer can’t look at anything else until they’ve absorbed the work in full.

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… The Autistic Experience

I was diagnosed circa 1975, when much less was known about autism and far fewer options were available to cope with the condition – CBD oil, for instance, can be an effective aid now, depending on the individual case, but there was no question of such things being available back then. If I do function as an autistic in a neurotypical world, that’s largely because my parents worked very hard with me over many years to help me do so, and I owe them a debt beyond measure.

I’m often asked if my condition has anything to do with my art. I think it does only in the sense that an artist has to include all of oneself in their work, or they’re not being honest as artists, to themselves or the viewer. Frida Kahlo discussed her physical injuries quite openly in her work, for instance, and her courage is a fine example to follow.

I do sometimes create pieces where I speak specifically, if symbolically, to the condition of being autistic: “The Quiet Moment” (2017) was specifically about the autistic experience, in that it depicts the need of people on the spectrum, in a world that can often painfully overwhelm them, for moments where they can escape from the overstimulation that can be a constant cross for us to bear.

I don’t take my work as evidence that autistics can do amazing things others can’t do; I think it says that we’re just as capable of doing amazing things as others are, and that the condition of autism, in an of itself, need not be a hinderance to such accomplishments.

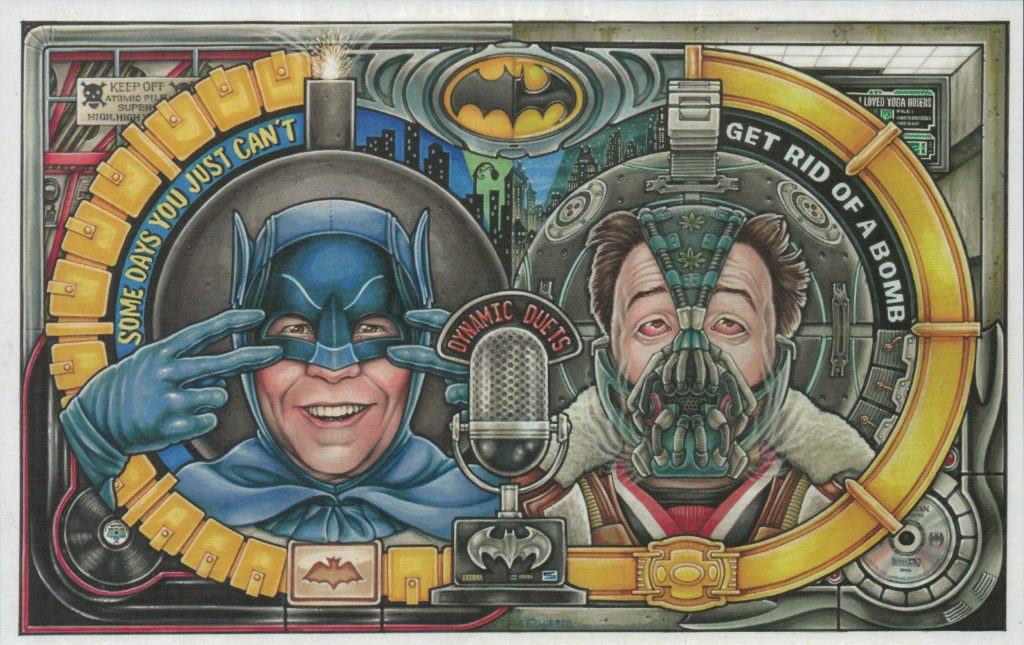

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… Kevin Smith

I have many influences, but I don’t have many role models, whose personal example I patterned my life choices on, and few of those are alive for me to meet and thank for the guidance they’d given me. Dali dies decades ago; Ligeti died before I could tell him that I’d loved his music from childhood; I wept when we lost Giger because his influence was that profound and I’d never have the chance to tell him what that had meant.

Kevin Smith inspired me by reminding me that I needed to love my art at a time when I didn’t, and I probably wouldn’t have started painting if not for that. And thanks to his close friend, actor and comedian Ralph Garman, who bought my work for Kevin as a Christmas gift three years ago, I was ultimately able to meet Kevin and thank him in a way I never could any of my other role models. And when artists you deeply respect you and your work in turn, there’s few greater experiences to be had anywhere, and it’s one I’ll be grateful to Ralph and Kevin for, probably for the rest of my life.

ERIK PFLUEGER ON… Soulmates

This series is fundamentally about relationships, and about how important it is to know the difference between the ideal and the reality within the relationship. That, at least, is the intellectual reason; on a more personal level, I dedicate this series to my wife, Yvette Smith Pflueger, who has proven not just my partner in this relationship, but also my best teacher in it.

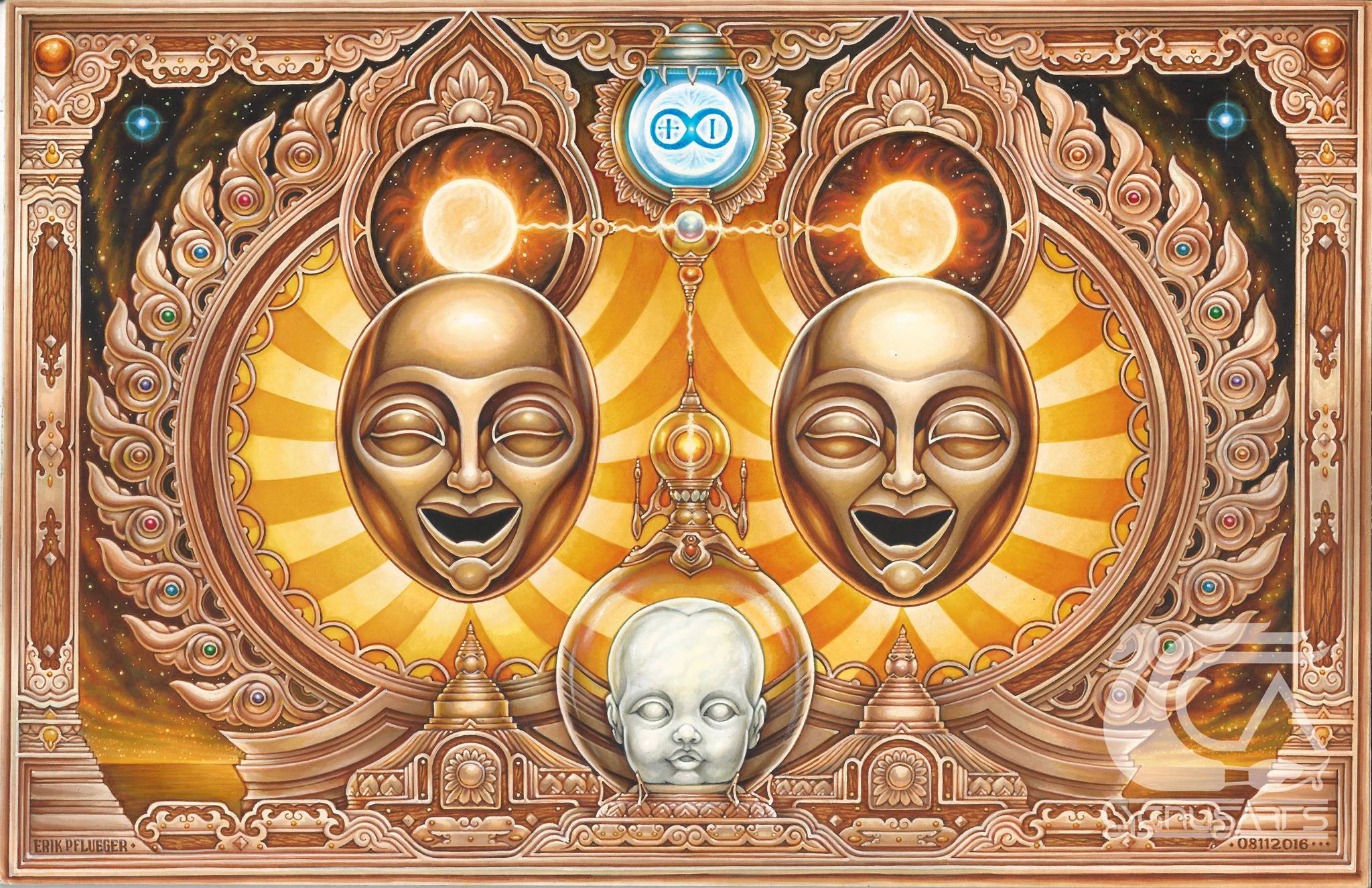

I: A PORTRAIT OF SOULMATES IN GOLD

This panel represents the ideal of the relationship, an ideal largely built on preconceptions and expectation brought in from before the relationship, but one that ultimately has no connection to the reality of what relationships are all about. That ideal, that innocent and naïve conception of the relationship, is represented by the bust of a baby’s head, and like an ideal, it is elevated accordingly, carved in marble, placed on a pedestal under glass. But until that conception breaks, things seem fine for the two soulmates in the relationship, represented by the masks, the design of which was taken from masks worn in Greek drama masks and from masks worn by Japanese samurai warriors. The faces of the soulmates are open, joyful, and they seem connected and in communication with each other.

I: A PORTRAIT OF SOULMATES IN RED

Preconceptions about a relationship tend to begin disintegrating the moment the first argument happens. As such, the baby’s head is burning, as the ideal burns away. The masks are covered in masks of their own, displaying the conflict of emotions; the outer masks are faced toward each other and display anger; the inner masks face away from each other and display pain and anguish. The communication between them has been corrupted and the mechanisms put in place for communication are breaking down.

I: A PORTRAIT OF SOULMATES IN BLUE

This is the cooling off period after the argument. The ideal of the relationship is reduced to a charred death’s head, but for a while one still tries to maintain the ideal: the skull is adorned like the Tibetan kapula skull. a last attempt at elevating the ideal. The soulmates are still separated, all communication is gone, and the walls are still up between them; the outer masks still face each other and display outwardly happy expressions. but the inner masks face outward and are flat in expression – outwardly, they pretend that things are fine between them, but inside they have not yet reconciled.

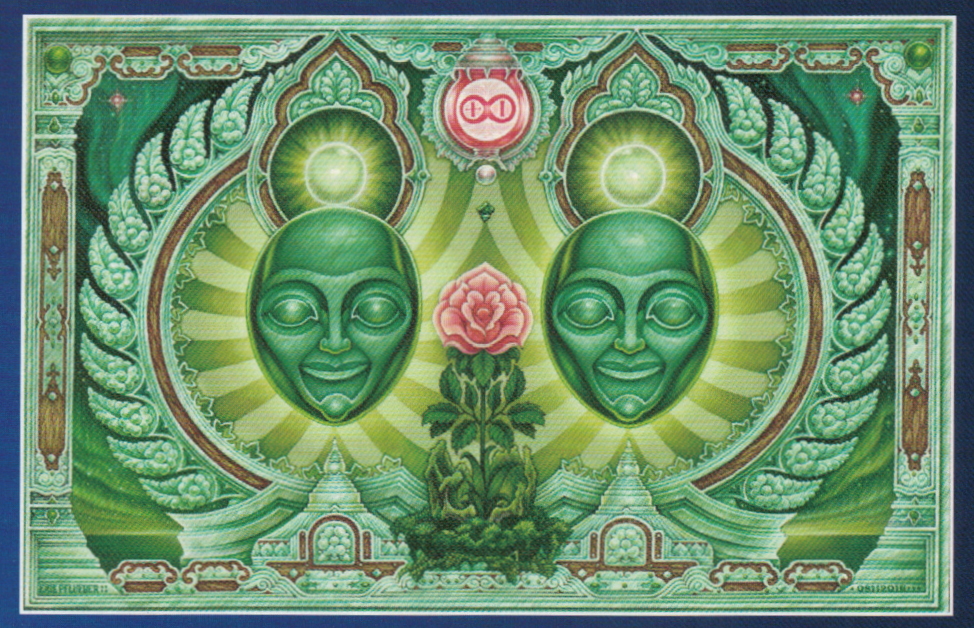

I: A PORTRAIT OF SOULMATES IN GREEN

This is the cooling off period after the argument. The ideal of the relationship is reduced to a charred death’s head, but for a while one still tries to maintain the ideal: the skull is adorned like the Tibetan kapula skull. a last attempt at elevating the ideal. The soulmates are still separated, all communication is gone, and the walls are still up between them; the outer masks still face each other and display outwardly happy expressions. but the inner masks face outward and are flat in expression – outwardly, they pretend that things are fine between them, but inside they have not yet reconciled.

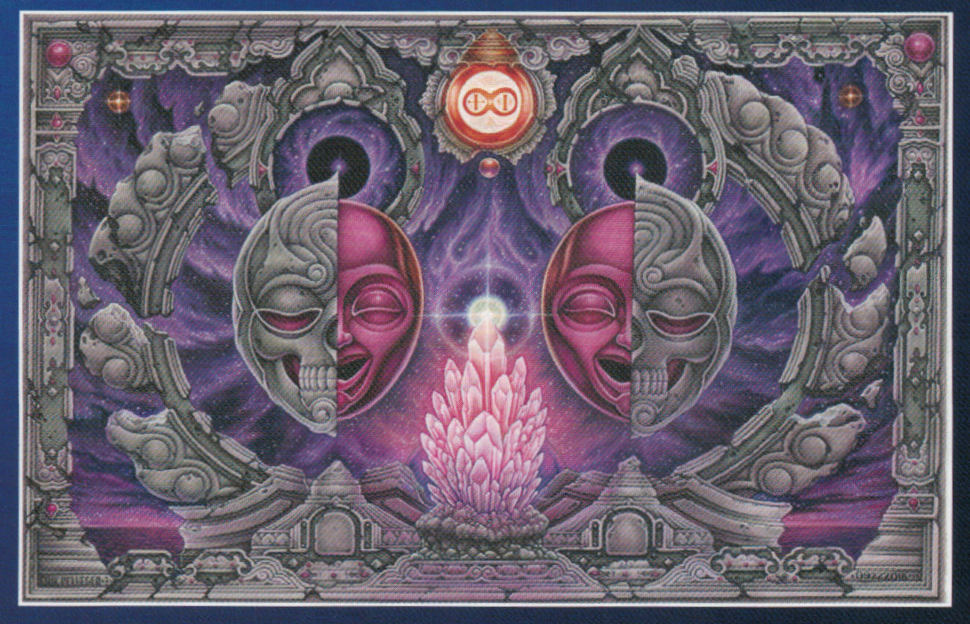

I: A PORTRAIT OF SOULMATES IN PURPLE

This is the cooling off period after the argument. The ideal of the relationship is reduced to a charred death’s head, but for a while one still tries to maintain the ideal: the skull is adorned like the Tibetan kapula skull. a last attempt at elevating the ideal. The soulmates are still separated, all communication is gone, and the walls are still up between them; the outer masks still face each other and display outwardly happy expressions. but the inner masks face outward and are flat in expression – outwardly, they pretend that things are fine between them, but inside they have not yet reconciled.

But the, that’s why they are soulmates to begin with.